Damage Limitation: Designing for mental disability

14 Mar 1993 - Blog

By Yasmin Shariff on March 1993 Building Housing Supplement

The charity MacIntyre, sets out to create reassuring spaces for mentally distressed children that allow a certain amount of deliberate battering. DSA director, Yasmin Shariff, describes how new design concepts have been put into practice in a residential school building in rural Wales.

Sensual Healing, the feature together with the one by Jeremy Myerson on Sensual Healing was published following the first conference held at the RIBA on Designing for people with mental disabilities organised by DSA in 1992.

“BEN’S JUST been dumped. There is no Care in the Community at all,” said Ben Silcock’s father as he tried to explain in front of the television cameras why his son jumped into the lion’s den at London Zoo in January.

Current Government policy requires most long-stay hospital wards for Ben and other people with mental disabilities to be closed. Unfortunately, not enough has been done to ensure that these people are rehoused in suitable accommodation.

Most are off-loaded into hostels where they are isolated and alienated, living on a diet of instant meals and TV. The care and stimulation needed to help them improve their condition and lead useful lives is often left to chance.

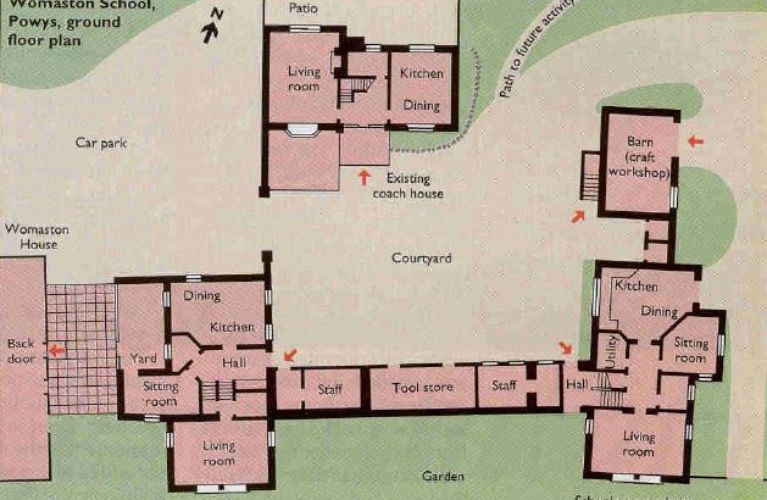

A good example of how care can be provided for people with mental disabilities sits deep in the rolling Welsh countryside. Womaston House is a white stucco, slate roofed Regency farmhouse, which was acquired by MacIntyre in 1987 to provide an educational, residential and therapeutic service for children with learning difficulties.

MacIntyre is one of the few organisations that cater specifically for people with mental disabilities and is dedicated to enabling children and adults to overcome their handicaps. A charity and voluntary organisation, it provides residential, day care and education & facilities in England and Wales. At Womaston, it was sought to provide homely alternatives to impersonal, overcrowded and devaluing institutional environments.

The house had already been partially converted and extended, but MacIntyre is now at the end of a three-year building programme which has radically improved both residential and educational spaces. Womaston is currently home to 23 young people aged between 9 and 19.

Helen Turner, one of Maclntyre’s carers involved in the initial design brief, describes the extraordinary problems that had to be overcome. “Children with learning difficulties want lo wind you up by being destructive,” she says. ‘The children need a lot of attention. If they’re not breaking one thing they’ll be breaking another.”

The challenge for architect John Money-Kyrle was to take into account these destructive forces without creating institutional concrete boxes. After the first residents moved into the farmhouse it became evident that the 2 m wide extension added by the previous owners encouraged many behavioural and spatial problems.

‘There are ‘dark’ spots in the classrooms, and the internal corridor is too narrow with inadequate natural light, making it gloomy and forbidding,” explains John Beckett, Maclntyre’s regional director.” Accommodation in the first floor flats was inadequate – spaces were too small and everyone was on top of each other. The children’s behaviour was at a high stress level. It became obvious that purpose-built houses had to be provided for them.”

There are few prototypes for this kind of accommodation and the brief developed by the architect and staff was continually adapted. At first glance the new homes do not appear to have any special features. But because of the inherent destructive tendencies of the residents, the design of the service elements, fixtures and fittings in the house had to be considered carefully. Vandal-resistant ironmongery, fixtures, fittings, sanitary installations, door and window openings have all been designed and selected with great care and attention to detail, with the result that the homes are neither bare nor institutional.

Significantly, the home’s staff and architect have not attempted to suppress totally the destructive behaviour but to limit the damage. There is a sacrificial layer of items which are easy to destroy but also easy to replace.

“The curtain heads were fixed with Velcro so that they can easily be pulled off. Because they are easy to fix, the children do not damage them as much as they used to when they were attached to a curtain rail,” says Turner.

Money-Kyrle devised other ingenious methods to deal with damage to more complicated elements such as the services installation. ”The main problems in the old house were bathrooms being flooded, destruction of pipes and fittings, and children scalding themselves with hot water.

“All of these problems have been overcome in the new development by providing features such as waterproof bathroom floors with drains, limiting valves on the hot water taps, concealed pipework. service ducts with secure access panels, ceiling panel heaters and the ability to turn water off from outside the bathroom”, he says.

Internally, the generous and well-lit circulation spaces give a warm, welcoming atmosphere. There are paintings, pottery and plants in the communal areas which create a homely character. All of these touches are placed just out of arm’s reach, so they do not get damaged easily.

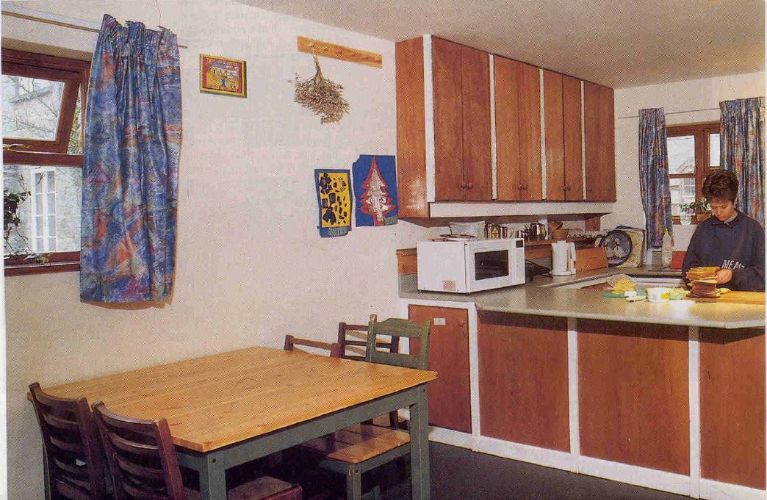

Even so, the living rooms, as with most hostel and student accommodation, tend to lack a personal feel. Window area has been restricted, presumably for financial or security reasons, with the result that these rooms tend to be gloomy. On the other hand, the kitchen and dining area has the warm feel of a traditional farmhouse kitchen.

Externally, the houses borrow from the existing farmhouse – white stucco wans and slate pitched roofs without resorting to vernacular pastiche. The link block of workshops and carer’s facilities between the two houses looks like a garden wall from one side. On the courtyard side this is expressed as a conservatory workshop.

Territorial factors were a major consideration in the design of the houses and the surrounding landscape. The definition of territory begins outside the houses, where there is the protected courtyard shared by both houses and workshops, and beyond this a lightly fenced front garden.

The courtyard is welcoming with communal areas of informal seating.

Flower beds add a splash of colour and soften the edges. The layout of the houses allows occupants to see clearly who is approaching the front door and what is happening in the courtyard.

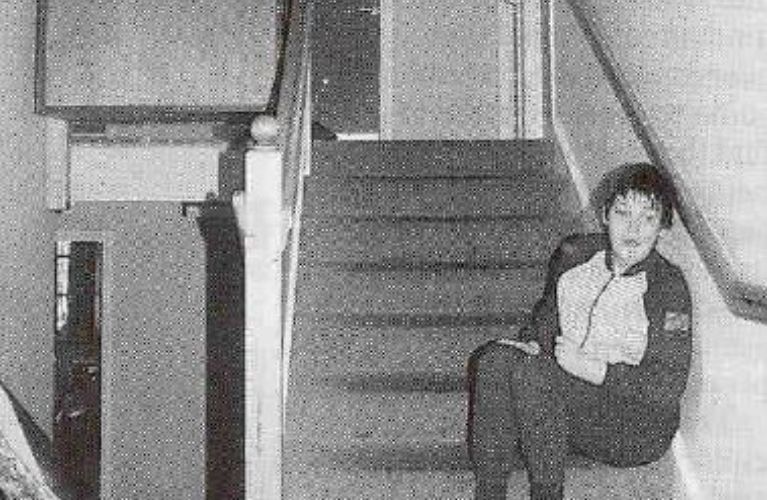

The entrance doors of the houses lead into a light and spacious central hall on a half landing. Steps lead down to the public areas or up to private bedrooms. The bedrooms are locked when the residents are out.

The lounge and dining rooms give access to a fenced private garden. The fences give a sense of privacy and containment, while the children are able to enjoy the view of rolling countryside at the end of the garden.

Various security devices have been tried on the entrance doors. “Initially an electrically-operated system was installed, but this was replaced by ordinary mortise locks because the area suffers from occasional power cuts which automatically released the locks and made the staff feel vulnerable,” says Turner.

The children are given responsibility for running their new home with their carers and are involved in all aspects of everyday home life, cooking, laundry, cleaning and shopping.

“Several approaches are used in Womaston to help young people realise their potential”, says Beckett.”Our institution is to turn problems into challenges. There is a fundamental belief that everyone can be creative in some way – our challenge is to find that way. In the process of being creative and achieving something, self confidence is increased. The new homes provide the residents with a secure base where this creative process begins.”

The approach of giving children responsibity has had some success. “Previously the children were destructive in their bedrooms, but when they movedinto their new homes their bedrooms became their prized possession, a private refuge lovingly decorated and furnished by each individual with the help of their carers.” Says turner

But Womaston and its residents does not survive in splendid isolation in the Welsh countryside. “MacIntyre makes full use of existing local facilities,” explains Beckett. “Residents attend youth clubs and, where appropriate, local schools. They take part in community events and festivals, and farming, gardening and hill walking are encouraged. Long walks can be excellent therapy for some of the children and young adults.

The next development planned at Womaston is a hall for sports, recreation and drama activities intended to complement local facilities. It is hoped that local residents will use the hall too.”

The building programme at Womaston has evolved with a client sensitive to the effects of design and a willingness to try out new ideas. The architect has been able to interpret the user s’ needs in terms of their physical and psychological requirements.

The warmth and care displayed in the design and detail of the buildings is touching. Even so, the refinement of the design has not added to the cost of the buildings: the first house was built for£813/ m2 (November 1989) and the second (with refinement) for£823/ m2 (March 1991).